Shortly after tackling the subject of game-to-film adaptations, I began to ponder something. If you were to compare my collection of films and videogames you'd find them approximately equal in number. And yet, if you were to calculate the difference in their initial retail value, you would probably find the games weighing in at least two, more likely even three times the cost of the films. Now I'll admit that my knowledge of the finance and production side of the film industry is very limited, and more so for game development, but even so, I cannot reconcile myself with the notion that this should be the case. As we shall see, none of the vague inferences that can be treated with a degree of certainty offer any compelling evidence in defence of such a pronounced discrepancy. To my mind it is simply a matter of evaluating the issue according to three simple points of comparison.

If we use my personal library as an example, we've established that the ratio of games to films is fairly balanced, while the initial retail value of the former is probably close to three times that of the latter, based on the fact that the price of a premium game title is generally three times that of your standard two-disc DVD at their time of release. If we were to add up the budgets invested in each title and then compare the two forms of media, however, I have no doubt that the discrepancy would be reversed, perhaps to the same order of magnitude, or even more, in favour of film. Whether it is due to a genuine lack of availability, or simply the product of lesser consumer interest, information regarding the size of a typical game budget is far less accessible than that of film, which is often the subject of widespread promotional use. Allowing for the inevitable exceptions, however, I find it difficult to imagine that the typical game budget would be on par with the sixty-five million dollar figure generally attributed to the average Hollywood production, let alone in excess of it. This is not even taking into account the matter of mammoth, blockbuster-aspiring budgets which inevitably become must-haves for your average movie enthusiast. Glancing over my own collection, the likes of Bram Stoker's Dracula, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy would have to come fairly close to balancing out my entire game library entirely on their own, as far as representing investment value is concerned. Adding further weight to this argument is the fact that the price of a typical two-disc DVD release fluctuates very little, despite the actual film budget, and quite often in adverse proportion to it. When you consider the initial cinema release, the point becomes still more pronounced, for it costs no more to see the latest big-budget extravaganza than it does to attend a small independent feature. Insofar as investment value is concerned then, there seems no reason why games should cost any more than your average DVD, let alone nearly triple the amount.

Comparing raw budget data is all well and good, but it's only fair to point out that the development of interactive media is very different from that of film, and thus incurs some unique expenses. One of the most frequently cited by game developers is the cost of development kits. With the industry dominated by three key players – Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo – the purportedly steep cost of the proprietary software required to make games for their respective consoles is largely unavoidable. In addition to this is the necessity of licensing and tailoring existing game engines to suit each specific project, or else incurring the additional time required to make your own from scratch. Then there is the fact that development time is often a good third to a half longer than that of your typical film, if not several times more. All of this must be taken into consideration, and yet, when we really do so, these differences amount to very little. Yes, game development involves a number of costs and considerations peculiar to itself, but then so does film. The time from pre-production to final release may be longer, but even the largest game developments involve far smaller crews than your typical film production. The cost of proprietary software may be an unavoidable expense, but this has its equivalent in the film industry too, including everything from the physical film and camera equipment, to proprietary editing software and the necessity of distributing through private cinema companies. The cost of subsequent distribution can be dismissed outright, as both games and film use exactly the same media, be it DVD, Blu-ray, or digital. Indeed, the game industry is generally able to avoid some of the more significant dents in a typical film budget, such as the cost of first-billing actors, the necessity of location fees, and the astronomical price of insurance at every level of filming. As such, the extent to which the game industry bewails its tenuous profitability on the basis of its unique expenses is a little hard to swallow.

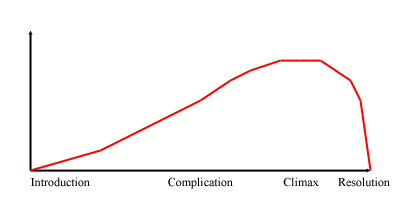

When you consider that the average film runs for about two hours, being able to play a game for up to ten to fifteen hours for only three times the price suddenly seems more reasonable. The way that games are marketed demonstrates that the industry is aware of the power of this suggestion, and the hope that, while games are not cheap, the consumer nevertheless feels they are getting good value. When you apply even a little critical though to this principle, however, it is immediately exposed as a fraud. In order to illustrate my point I would like to turn your attention to the image below. There we see three forms of media dealing with the same license: a film, a television series, and a game all based on the popular Terminator franchise. Despite widespread criticism of the game for its short length, someone intending to buy the upcoming Terminator: Salvation DVD might still justify the full retail price of the game with the assurance that they are getting at least two-and-a-half times the duration of the film out of it, meaning that they cost roughly the same to experience per hour. First of all, this ignores the obvious fact that most people do not buy a DVD when they only intend to watch a film once. Secondly, how do we apply this measure of value to the television series, which extends to roughly twice the length of the game, and five times the length of the film? Surely if the measure of value is duration, then longer films should be more expensive, or else priced according to the number of times someone is likely to watch it. The principle is even less convincing when it comes to games, for there is no consistent ratio between the amount of effort and expenditure that is invested in a title and the amount of time it is likely to be played by the consumer. If this were true, the cost of something as simple as Tetris, with no real limit to the experience, should be more expensive than the Terminator: Salvation game. For that matter, how could one compare a sandbox game, where you are simply presented with a set of tools and then allowed to entertain yourself, to another where meticulous effort has gone into crafting a story of more limited duration?

For an outsider, with little real knowledge of the game industry, it is difficult to pinpoint where the profit from the exorbitant cost of games is going. However, with Sony openly admitting to the fact that it incurs a loss with every Playstation 3 console it produces, and Microsoft able to absorb the cost of an endemic failure rate in its Xbox 360, it is certain that the profit margins carved out of software sales must be playing a significant role in keeping their operations viable. The seemingly endless cycle of acquisition, merging, and disbanding of game development studios, despite the continued profits of large publishing companies is also conspicuous, even where specific titles have performed admirably on the market. And while the developers may deserve our sympathy for having much of the risk and little of the reward for each project passed squarely onto them, it is the consumer who ultimately pays. Indeed, the only point of difference that appears to have any real merit in the price discrepancy between games and film is the size of the market. Though they are cheaper to make, games simply don't have the same market share as the lucrative film industry, so in order to derive similar margins, the price is set universally high. In effect, people who buy games are paying a subsidy to the industry on behalf of all those who don't, which has the subsequent affect of discouraging new consumers. Still, if everyone woke up tomorrow a certified gamer would anyone seriously expect the price of games to fall accordingly? There is simply no incentive to lower prices when so many are prepared to pay.

Investment

If we use my personal library as an example, we've established that the ratio of games to films is fairly balanced, while the initial retail value of the former is probably close to three times that of the latter, based on the fact that the price of a premium game title is generally three times that of your standard two-disc DVD at their time of release. If we were to add up the budgets invested in each title and then compare the two forms of media, however, I have no doubt that the discrepancy would be reversed, perhaps to the same order of magnitude, or even more, in favour of film. Whether it is due to a genuine lack of availability, or simply the product of lesser consumer interest, information regarding the size of a typical game budget is far less accessible than that of film, which is often the subject of widespread promotional use. Allowing for the inevitable exceptions, however, I find it difficult to imagine that the typical game budget would be on par with the sixty-five million dollar figure generally attributed to the average Hollywood production, let alone in excess of it. This is not even taking into account the matter of mammoth, blockbuster-aspiring budgets which inevitably become must-haves for your average movie enthusiast. Glancing over my own collection, the likes of Bram Stoker's Dracula, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy would have to come fairly close to balancing out my entire game library entirely on their own, as far as representing investment value is concerned. Adding further weight to this argument is the fact that the price of a typical two-disc DVD release fluctuates very little, despite the actual film budget, and quite often in adverse proportion to it. When you consider the initial cinema release, the point becomes still more pronounced, for it costs no more to see the latest big-budget extravaganza than it does to attend a small independent feature. Insofar as investment value is concerned then, there seems no reason why games should cost any more than your average DVD, let alone nearly triple the amount.

Expenditure

Comparing raw budget data is all well and good, but it's only fair to point out that the development of interactive media is very different from that of film, and thus incurs some unique expenses. One of the most frequently cited by game developers is the cost of development kits. With the industry dominated by three key players – Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo – the purportedly steep cost of the proprietary software required to make games for their respective consoles is largely unavoidable. In addition to this is the necessity of licensing and tailoring existing game engines to suit each specific project, or else incurring the additional time required to make your own from scratch. Then there is the fact that development time is often a good third to a half longer than that of your typical film, if not several times more. All of this must be taken into consideration, and yet, when we really do so, these differences amount to very little. Yes, game development involves a number of costs and considerations peculiar to itself, but then so does film. The time from pre-production to final release may be longer, but even the largest game developments involve far smaller crews than your typical film production. The cost of proprietary software may be an unavoidable expense, but this has its equivalent in the film industry too, including everything from the physical film and camera equipment, to proprietary editing software and the necessity of distributing through private cinema companies. The cost of subsequent distribution can be dismissed outright, as both games and film use exactly the same media, be it DVD, Blu-ray, or digital. Indeed, the game industry is generally able to avoid some of the more significant dents in a typical film budget, such as the cost of first-billing actors, the necessity of location fees, and the astronomical price of insurance at every level of filming. As such, the extent to which the game industry bewails its tenuous profitability on the basis of its unique expenses is a little hard to swallow.

Duration

For an outsider, with little real knowledge of the game industry, it is difficult to pinpoint where the profit from the exorbitant cost of games is going. However, with Sony openly admitting to the fact that it incurs a loss with every Playstation 3 console it produces, and Microsoft able to absorb the cost of an endemic failure rate in its Xbox 360, it is certain that the profit margins carved out of software sales must be playing a significant role in keeping their operations viable. The seemingly endless cycle of acquisition, merging, and disbanding of game development studios, despite the continued profits of large publishing companies is also conspicuous, even where specific titles have performed admirably on the market. And while the developers may deserve our sympathy for having much of the risk and little of the reward for each project passed squarely onto them, it is the consumer who ultimately pays. Indeed, the only point of difference that appears to have any real merit in the price discrepancy between games and film is the size of the market. Though they are cheaper to make, games simply don't have the same market share as the lucrative film industry, so in order to derive similar margins, the price is set universally high. In effect, people who buy games are paying a subsidy to the industry on behalf of all those who don't, which has the subsequent affect of discouraging new consumers. Still, if everyone woke up tomorrow a certified gamer would anyone seriously expect the price of games to fall accordingly? There is simply no incentive to lower prices when so many are prepared to pay.