Perhaps the steady promotion of the term 'graphic novel' had something to do with it, perhaps a genuine maturation of the medium itself, or perhaps it all comes down to generational succession, but whatever the cause, it is undeniable that the past ten years have seen a fundamental shift in the attitude toward comic book adaptations. With a growing catalogue of entries whose diversity encompasses the likes of From Hell and V for Vendetta at one extreme, Sin City and 300 somewhere in the middle, and The Dark Knight and Iron Man at the other, it seems that the entire spectrum from revisionist to classic superhero material has finally attained credence with the mainstream audience. No longer the sole province of PG-13 summer movie fare, comic book adaptations frequently set new records in terms of revenue, and elicit acknowledgement from even the most recalcitrant film critics.

When you consider that the roots of the modern comic book were laid down during the pulp era of the 1930s, however, the recent success of film adaptations is clearly nowhere near as sudden or effortless as it may otherwise appear. The fact that we even entertain the idea of comic-based films having themes and dealing with real issues at the present time is really the product of a seventy-odd year campaign to gain serious recognition, one characterised by much trial and even more error. And if we may now safely claim that the comic book film is nearing the end of its turbulent adolescence, to show the first brief glimpses of real maturity, then it can also be rightly said to have simply passed the baton on to its younger sibling: the still-fledging medium of videogames. At nearly a half-century younger than the earliest comic books, it is perhaps no surprise that game-based films have yet to garner much in the way of critical approval, nor have the vast majority shown sufficient merit to warrant it, despite some financial success.

So are we destined to endure another thirty years before videogame adaptations start to find their feet, as we did with with comic-based films? Does the videogame medium present qualities which might either accelerate or delay the point of mainstream acceptance? Where have current adaptations gone right and/or wrong during their transition to the screen? In this series of articles I intend to examine some of the fundamental factors involved.

Despite their apparent similarity, one of the fundamental differences between the film and videogame mediums lie in the way their narrative unfolds. This has much to do with the fact that the earliest videogames were entirely devoid of all but the most cursory semblance of a storyline, assuming they made any pretence at all. Pong and its antecedents were obviously simulations of existing recreational games, and thus required no premise at all. Later games often featured a premise that could be reduced to a single line – rarely imparted, even through text, within the game itself – and exhibited none of the subsequent development which might be deemed an actual plot. Space Invaders, for example, established your raison d'etre as the only defence against an alien offensive and simply left you to accomplish that task. This template would continue well into the early '90s, including such staples as Super Mario Bros. and Sonic the Hedgehog, with a paragraph in the game manual often providing the sole indication of an underlying story.

This trend was due partly to technological limitations, of course, at a time when full-motion cutscenes and recorded dialogue were considered a tremendous luxury, but it was also a product of what was considered a redundancy. The player's ability to enjoy Space Invaders is not at all dependent upon whether or not they heed what little semblance of a plot it conveys, nor is their progress inhibited should they choose to ignore it. Indeed, while the aesthetic dimension of gaming has advanced tremendously up to the present day, the core dynamics of gameplay have necessarily remained largely unchanged. The fundamental experience still boils down to a matter of learning what the inherent rules may be within the closed boundaries of the game and how best to exploit them in order to progress. It is the same fundamental process we encounter in sports, board and card games, and any other abstract activity defined by arbitrary rules. And just as there is no reason to think that a tennis match would necessarily be enhanced by the presence of an underlying storyline, there is no reason why videogames cannot be enjoyed solely as a form of interactive, skill-based entertainment. The fact that games generally are married with traditional storytelling does not, however, automatically ease their transition onto the screen.

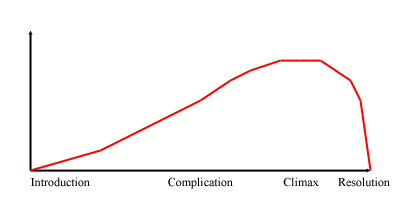

The graph above shows a typical visualisation of the dynamics within traditional storytelling, and is equally applicable to literature, theatre, and film. At its simplest, the development of plot is this fashion can generally be reduced to a mere three propositions, for example: the cat sat on the mat; a dog entered the room and scared it; the cat hissed and the dog ran away. All but the most rudimentary games of the past forty years impart something equivalent to this, albeit with one crucial qualification. Space Invaders, for instance, can be summarised as follows: aliens launch an invasion; a single tank retaliates; the alien forces are defeated. The crucial difference is that the final clause, and therefore the actual development of the story, depends entirely upon the player's ability to progress through the game. Our attention to the storyline is relegated to the status of a secondary concern next to our ability to apprehend the skills needed to successfully negotiate the gameplay. As such, there are really two dynamics at work in the modern game experience.

Obviously Space Invaders can only illustrate a point so far, and in order to fully explain this point I'd like to turn your attention to the more recent Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. For those of you unfamiliar with the Prince of Persia series, The Sands of Time drew great acclaim among videogame critics for its combination of interesting gameplay mechanics and engaging narrative. What made the former unique was the ability to manipulate time in various ways, combined with an increasingly spectacular array of gymnastic abilities required of the protagonist. Death-defying leaps, running along walls, and vaulting over multiple opponents were all enhanced by the ability to slow down, freeze, or even rewind gameplay itself. Not only were these conceits justified through the narrative – where they were established as the effects of several enchanted artefacts – but the storytelling itself actually managed to imbue the mechanics with a level of dramatic significance. In short, the game itself was presented under the guise of a tale being narrated by the protagonist to another character, with failure resulting in a hasty exclamation of “No, no, no, that isn't how it happened. Let me begin again...”. The interactive, branching nature of the gameplay was thus incorporated into the narrative itself, preserving the player's immersion within the continuity of the storyline without hampering the interactive experience.

In many ways, The Sands of Time represents a perfect candidate for a big-screen adaptation, and it is no surprise that this is currently taking place. While the nature of the game makes it particularly conducive to translation onto film, however, this is still no guarantee of success. The problem is that all videogames contain a fundamental dualism. There is no question that the vast majority now impart something very close to the classic model of narrative development, but the means of revealing this aspect continues to be dependant upon a system of geometric progression, which we generally refer to as gameplay. This is what we see in the graph above, where the stepped line representing gameplay imparts the shadow of a classic story arc through their intersection at various points. Overall, the majority of the typical game experience consists of incremental repetition. This is not a bad thing, in fact it is the hallmark of the most well-constructed games, and probably encountered this concept before, under the misleading guise of the term 'difficulty curve': you learn action X; the game offers a few instances of increasing difficulty where X is required; you progress. You learn action Y, the game offers a few instances of increasing difficulty where Y is required, you progress. By increments, the end of the game would see you performing increasingly complex variations: XX, XY, YX, XYX, XYZ and so on. This is necessary in order for the player to be able to progress, but it does not make for compelling viewing. Indeed, what makes up the majority of the gameplay experience is the kind of incremental repetition that is generally conflated to form a montage in film.

The underlying issue, then, is whether it is the gameplay or narrative that is defined as the quintessential characteristic of the videogame experience: that presumably being the element worthy of adaptation in the first place. In most cases the answer lies in finding the appropriate balance between the two. For, just as it would lose something of its defining characteristics if The Sands of Time did not contain a few scenes of wall-running, acrobatic fighting, and time manipulation, it would be a tedious experience if it featured little else.

When you consider that the roots of the modern comic book were laid down during the pulp era of the 1930s, however, the recent success of film adaptations is clearly nowhere near as sudden or effortless as it may otherwise appear. The fact that we even entertain the idea of comic-based films having themes and dealing with real issues at the present time is really the product of a seventy-odd year campaign to gain serious recognition, one characterised by much trial and even more error. And if we may now safely claim that the comic book film is nearing the end of its turbulent adolescence, to show the first brief glimpses of real maturity, then it can also be rightly said to have simply passed the baton on to its younger sibling: the still-fledging medium of videogames. At nearly a half-century younger than the earliest comic books, it is perhaps no surprise that game-based films have yet to garner much in the way of critical approval, nor have the vast majority shown sufficient merit to warrant it, despite some financial success.

So are we destined to endure another thirty years before videogame adaptations start to find their feet, as we did with with comic-based films? Does the videogame medium present qualities which might either accelerate or delay the point of mainstream acceptance? Where have current adaptations gone right and/or wrong during their transition to the screen? In this series of articles I intend to examine some of the fundamental factors involved.

Films develop, games progress

Despite their apparent similarity, one of the fundamental differences between the film and videogame mediums lie in the way their narrative unfolds. This has much to do with the fact that the earliest videogames were entirely devoid of all but the most cursory semblance of a storyline, assuming they made any pretence at all. Pong and its antecedents were obviously simulations of existing recreational games, and thus required no premise at all. Later games often featured a premise that could be reduced to a single line – rarely imparted, even through text, within the game itself – and exhibited none of the subsequent development which might be deemed an actual plot. Space Invaders, for example, established your raison d'etre as the only defence against an alien offensive and simply left you to accomplish that task. This template would continue well into the early '90s, including such staples as Super Mario Bros. and Sonic the Hedgehog, with a paragraph in the game manual often providing the sole indication of an underlying story.

|

| Great fun, but no real pathos |

|

| Typical narrative structure |

Obviously Space Invaders can only illustrate a point so far, and in order to fully explain this point I'd like to turn your attention to the more recent Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. For those of you unfamiliar with the Prince of Persia series, The Sands of Time drew great acclaim among videogame critics for its combination of interesting gameplay mechanics and engaging narrative. What made the former unique was the ability to manipulate time in various ways, combined with an increasingly spectacular array of gymnastic abilities required of the protagonist. Death-defying leaps, running along walls, and vaulting over multiple opponents were all enhanced by the ability to slow down, freeze, or even rewind gameplay itself. Not only were these conceits justified through the narrative – where they were established as the effects of several enchanted artefacts – but the storytelling itself actually managed to imbue the mechanics with a level of dramatic significance. In short, the game itself was presented under the guise of a tale being narrated by the protagonist to another character, with failure resulting in a hasty exclamation of “No, no, no, that isn't how it happened. Let me begin again...”. The interactive, branching nature of the gameplay was thus incorporated into the narrative itself, preserving the player's immersion within the continuity of the storyline without hampering the interactive experience.

|

| Gameplay progression |

The underlying issue, then, is whether it is the gameplay or narrative that is defined as the quintessential characteristic of the videogame experience: that presumably being the element worthy of adaptation in the first place. In most cases the answer lies in finding the appropriate balance between the two. For, just as it would lose something of its defining characteristics if The Sands of Time did not contain a few scenes of wall-running, acrobatic fighting, and time manipulation, it would be a tedious experience if it featured little else.